Preparing for the Collapse of the Petrodollar System, Part 1

Recently, there have been many news headlines containing the words “Iran”, “nuclear capability”, “Syria”, and “Islamic State”. If you listen closely, you can almost hear the drumbeats of a fresh war in the Middle East.

As an economist, I have been trained to view the world through the lens of incentives. (I am a “bottom line” kind of guy.) And just as every action is motivated by an underlying incentive, every decision has a related consequence.

This brief article details the actions, incentives, and related consequences that the United States has created through its attempts to maintain global hegemony through something known as the petrodollar system.

This article will begin with a look back at the important events of the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference, which firmly established the U.S. Dollar as the global reserve currency. Then we will examine the events that led up to the 1971 Nixon Shock when the United States abandoned the international gold standard. We will then consider what may be the most brilliant economic and geopolitical strategy devised in recent memory, the petrodollar system.

Finally, we conclude by examining the latest challenges facing U.S. economic policy around the globe and how the petrodollar system influences our foreign policy efforts in oil-rich nations. The collapse of the petrodollar system, which I believe will occur sometime within this decade, will make the 1971 Nixon Shock look like a dress rehearsal.

If you have never heard of the petrodollar system, it will not surprise me. It is certainly not a topic that makes its way out of Washington and Wall Street circles too often. The mainstream media rarely, if ever, discusses the inner workings of the petrodollar system and how it has motivated, and even guided, America’s foreign policy in the Middle East for the last several decades.

Personal Note: What I am going to explain in this article is something that I believe is vitally important for every American to understand. Since 2006, I have written dozens of articles on the petrodollar system. I have appeared on many major news media outlets talking about the petrodollar system. I even wrote a best-selling book entitled Bankruptcy of our Nation that spends an entire chapter exposing the petrodollar system. I have spoken about this topic all over the world. Suffice it to say, I believe that understanding the petrodollar system is very important to your financial well-being. I encourage you to print this article out and read it carefully. When you are finished with it, I encourage you to share it with your friends and neighbors. Share it on Facebook and Twitter. Help us get the word out so that the American public can stir from its slumber and begin preparing for what lies ahead.

A Brief Overview of this Series on the Petrodollar System

In the final days of World War II, 44 leaders from all of the Allied nations met in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire in an effort to create a new global economic order. With much of the global economy decimated by the war, the United States emerged as the world’s new economic leader. The relatively young and economically nimble U.S. served as a refreshing replacement to the globe’s former hegemon: a debt-ridden and war-torn Great Britain.

In addition to introducing a number of global financial agencies, the historic meeting also created an international gold-backed monetary standard which relied heavily upon the U.S. Dollar.

Initially, this dollar system worked well. However, by the 1960’s, the weight of the system upon the United States became unbearable. On August 15, 1971, President Richard M. Nixon shocked the global economy when he officially ended the international convertibility from U.S. dollars into gold, thereby bringing an official end to the Bretton Woods arrangement.

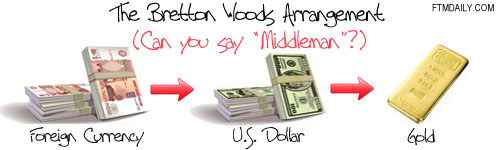

Two years later, in an effort to maintain global demand for U.S. dollars, another system was created called the petrodollar system. In 1973, a deal was struck between Saudi Arabia and the United States in which every barrel of oil purchased from the Saudis would be denominated in U.S. dollars. Under this new arrangement, any country that sought to purchase oil from Saudi Arabia would be required to first exchange their own national currency for U.S. dollars. In exchange for Saudi Arabia’s willingness to denominate their oil sales exclusively in U.S. dollars, the United States offered weapons and protection of their oil fields from neighboring nations, including Israel.

By 1975, all of the OPEC nations had agreed to price their own oil supplies exclusively in U.S. dollars in exchange for weapons and military protection.

This petrodollar system, or more simply known as an “oil for dollars” system, created an immediate artificial demand for U.S. dollars around the globe. And of course, as global oil demand increased, so did the demand for U.S. dollars.

As the U.S. dollar continued to lose purchasing power, several oil-producing countries began to question the wisdom of accepting increasingly worthless paper currency for their oil supplies. Today, several countries have attempted to move away, or already have moved away, from the petrodollar system. Examples include Iran, Syria, Venezuela, and North Korea… or the “axis of evil,” if you prefer. (What is happening in our world today makes a whole lot of sense if you simply read between the lines and ignore the “official” reasons that are given in the mainstream media.) Additionally, other nations are choosing to use their own currencies for oil like China, Russia, and India, among others.

As more countries continue to move away from the petrodollar system which uses the U.S. dollar as payment for oil, we expect massive inflationary pressures to strike the U.S. economy. In this article, we will explain how this could be possible.

The Coming Collapse of the Petrodollar System

When historians write about the year 1944, it is often dominated with references to the tragedies and triumphs of World War II. And while 1944 was truly a pivotal year in one of history’s most devastating conflicts of all time, it was also a significant year for the international economic system. In July of that same year, the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference (more commonly known as the Bretton Woods conference) was held in the Mount Washington hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. The historic gathering included 730 delegates from 44 Allied nations. The aim of the meeting was to regulate the war-torn international economic system.

During the three-week conference, two new international bodies were established.

These included:

- The International Bank of Reconstruction and Development (IBRD, later known as the World Bank)

- The International Monetary Fund

In addition, the delegates introduced the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT, later known as the World Trade Organization, or WTO.)

More importantly, for our purposes here, another development that emerged from the conference was a new fixed exchange rate regime with the U.S. Dollar playing a central role. In essence, all global currencies were pegged to the U.S. Dollar.

At this point, an appropriate question to be asking yourself is: ”Why would all of the nations be willing to allow the value of their currencies to be dependent upon the U.S. Dollar?”

The answer is quite simple.

The U.S. Dollar would be pegged at a fixed rate to gold. This made the U.S. dollar completely convertible into gold at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce within the global economic community. This international convertibility into gold allayed concerns about the fixed rate regime and created a sense of financial security among nations in pegging their currency’s value to the dollar. After all, the Bretton Woods arrangement provided an escape hatch: if a particular nation no longer felt comfortable with the dollar, they could easily convert their dollars holdings into gold. This arrangement helped restore a much-needed stability in the financial system. But it also accomplished one other very important thing. The Bretton Woods agreement instantly created a strong global demand for U.S. dollars as the preferred medium of exchange.

And along with this growing demand for U.S. Dollars came the need for… a larger supply of dollars.

Now, before we continue this discussion, stop for a moment and ask yourself this question: Are there any obvious benefits from creating more dollars? And if so, who benefits?

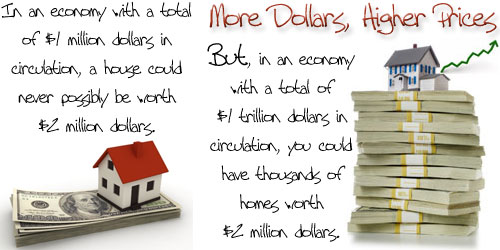

First, the creation of more dollars allows for the inflation of asset prices. In other words, more dollars in existence allows for a rise in overall prices.

For example, imagine for a moment if the U.S. economy had a total money supply of only $1 million dollars. What if, in this imaginary economy, I attempted to sell you my home for $2 million dollars? While you may like my home, and may even want to buy it, it would be physically impossible for you to do so. And it would be completely absurd for me to ask for $2 million because, in our imaginary economy, there is only $1 million in existence.

So an increase in the overall money supply allows asset prices to rise.

But that’s not all.

The United States government benefits from a global demand for U.S. dollars. How? It’s because a global demand for dollars gives the Federal government a “permission slip” to print more. After all, we can’t let our global friends down, can we? If they “need” dollars, then let’s print some more dollars for them.

Is it a coincidence that printing dollars is the U.S. government’s preferred method of dealing with our nation’s economic problems?

Remember, Washington only has four basic ways to solve its economic problems:

1. Increase income by raising taxes on the citizens

2. Cut spending by reducing benefits

3. Borrow money through the issuance of government bonds

4. Print money

Raising taxes and making meaningful spending cuts can be political suicide. Borrowing money is a politically convenient option, but you can only borrow so much. That leaves the final option of printing money. Printing money requires no immediate sacrifice and no spending cuts. It’s a perfect solution for a growing country that wants to avoid making any sacrifices. However, printing more money than is needed can lead to inflation. Therefore, if a country can somehow generate a global demand for its currency, it has a “permission slip” to print more money. Understanding this “permission slip” concept will be important as we continue.

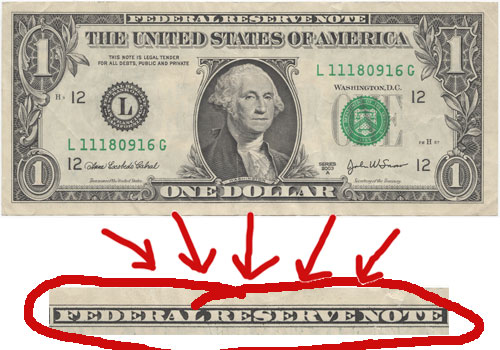

Finally, the primary beneficiary of an increased global demand for the U.S. Dollar is America’s central bank, the Federal Reserve. If this does not make immediate sense, then pull out a dollar bill from your wallet or purse and notice whose name is plastered right on the top of it.

Have you ever asked yourself why the U.S. Dollar is called a Federal Reserve Note?

Once again, the answer is simple.

The U.S. Dollar is issued and loaned to the United States government by the Federal Reserve.

Because our dollars are loaned to our government by the Federal Reserve, which is a private central banking cartel, the dollars must be paid back. And not only must the dollars be paid back to the Federal Reserve. They must be paid back with interest!

And who sets the interest rate targets on the loaned dollars? It’s the Federal Reserve, of course.

To put it simply, the Federal Reserve has a clear vested interest in maintaining a stable and growing global demand for U.S. Dollars because they create them and then earn profit from them with interest rates which they set themselves. What a great system the Federal Reserve has for itself. No wonder it hates oversight and intervention. No wonder the private banking cartel that runs the Federal Reserve despises all attempts to actually audit its books.

In summary, the American consumer, the Federal government, and Federal Reserve all benefit to varying degrees from a global demand for U.S. Dollars.

The Bretton Woods Breakdown: Vietnam, The Great Society, and Deficit Spending

There is an old saying that goes, “He who holds the gold makes the rules.” This statement has never been truer than in the case of America in the post-World War II era. By the end of the war, nearly 80 percent of the world’s gold was sitting in U.S. vaults, and the U.S. Dollar had officially become the world’s undisputed reserve currency.

As a result of the Bretton Woods arrangement, the dollar was considered to be “as safe as gold.”

A study of the United States economy in the post-World War II era demonstrates that this was a time of dramatic economic growth and expansion. This era gave rise to the baby boomer generation. By the late 1960’s, however, the American economy was under major pressure. Deficit spending in Washington was uncontrollable as President Lyndon B. Johnson began to realize his dream of a “Great Society.”With the creation of Medicare and Medicaid, American citizens could now, for the first time, earn a living from their government.

Meanwhile, an expensive and unpopular war in Vietnam funded by record deficit spending led some nations to question the economic underpinnings of America.

After all, the entire global economic order had become dependent upon a sound U.S. economy. Countries like Japan, Germany, and France, while fully on the mend from the devastation of World War II, were still largely dependent upon a financially stable American economy to maintain their economic growth.

By 1971, as America’s trade deficits increased and its domestic spending soared, the perceived economic stability of Washington was being publicly challenged by many nations around the globe. Foreign nations could sense the severe economic difficulties mounting in Washington as the United States was under financial pressure at home and abroad. According to most estimates, the Vietnam War had a price tag in excess of $200 billion. This mounting debt, plus other debts incurred through a series of poor fiscal and monetary policies, was highly problematic given America’s global monetary role.

But it was not America’s financial issues that most concerned the international economic community. Instead, it was the growing imbalance of U.S. gold reserves to debt levels that was most alarming.

The United States had accumulated large amounts of new debt but did not have the money to pay for them. Making matters worse, U.S. gold reserves were at all-time lows as nation after nation began requesting gold in exchange for their dollar holdings. It was almost as if foreign nations could see the writing on the wall for the end of the Bretton Woods arrangement.

As 1971 progressed, so did foreign demand for U.S. gold. Foreign central banks began cashing in their excess dollars in exchange for the safety of gold. As nations lined up to exchange their dollar holdings for Washington’s gold, the United States realized that the game was over. Clearly, America had never intended to be the globe’s gold warehouse. Instead, the convertibility of the dollar into gold was meant to generate a global trust in U.S. paper money. Simply knowing that the U.S. dollar could be converted into gold if necessary was good enough for some — but not for everyone. The nations which began to doubt America’s ability to manage their own finances decided to opt for the recognized safety of gold. (Historically, gold has been, and will likely remain, the beneficiary of poor fiscal and monetary policies, and 1971 was no different.)

One would have expected that the large and growing demand by foreign nations for gold instead of dollars would have been a strong indicator to the United States to get its fiscal house in order. Instead, America did exactly the opposite. As Washington continued racking up enormous debts to fund its imperial pursuits and its over-consumption, foreign nations sped up their demand for more U.S. gold and fewer U.S. dollars. Washington was caught in its own trap and was required to supply real money (gold) in return for the inflows of their fake paper money (U.S. dollars).

They had been hamstrung by their own imperialistic policies.

Soon the United States was bleeding gold. Washington knew that the system was no longer viable, and certainly not sustainable. But what could they do to stem the crisis? There were only two options.

The first option would require that Washington immediately reduce its massive spending and dramatically reduce its existing debts. This option could possibly restore confidence in the long-term viability of the U.S. economy. The second option would be to increase the dollar price of gold to accurately reflect the new economic realities. There was an inherent flaw in both of these options that made them unacceptable to the United States at the time… they both required fiscal restraint and economic responsibility. Then, as now, there was very little appetite for reducing consumption in the beleaguered name of “sacrifice” or “responsibility.”

Goodbye, Yellow Brick Road

The Bretton Woods system created an international gold standard with the U.S. dollar as the ultimate beneficiary. But in an ironic twist of fate, the system that was designed to bring stability to a war-torn global economy was threatening to plunge the world back into financial chaos. The gold standard created by Bretton Woods simply could not bear the financial excesses, coupled with the imperialistic pursuits, of the American economic empire.

On August 15, 1971, under the leadership of President Richard M. Nixon, Washington chose to maintain its reckless consumption and debt patterns by detaching the U.S. Dollar from its convertibility into gold. By “closing the gold window,” Nixon destroyed the final vestiges of the international gold standard. Nixon’s decision effectively ended the practice of exchanging dollars for gold, as directed under the Bretton Woods agreement. It was in this year, 1971, that the U.S. dollar officially abandoned the gold standard and was declared a purely “fiat” currency. (A “fiat” currency is one that derives it value from its sponsoring government. It is a currency issued and accepted by decree.)

Here’s a brief 2-minute excerpt of the actual televised speech delivered by President Nixon on August 15, 1971 in which he ended the U.S. Dollar’s convertibility into gold.

As all other fiat empires before it, Washington had come to view gold as a constraint to their colossal spending urges. A gold standard, as provided by the Bretton Woods system, meant that America had to attempt to publicly demonstrate fiscal restraint by maintaining holistic economic balance.

By “closing the gold window,” Washington had affected not only American economic policy — it also affected global economic policy. Under the international gold standard of Bretton Woods, all currencies derived their value from the value of the dollar. And the dollar derived its value from the fixed price of its gold reserves. But when the dollar’s value was detached from gold, it became what economists call a “floating” currency. (By “floating,” it is meant that the currency is not attached, nor does it derive its value, from anything externally.) Put simply, a “floating” currency is a currency that is not fixed in value.

Like any commodity, the dollar could be affected by the market forces of supply and demand. When the dollar became a “floating” currency, the rest of the world’s currencies, which had been previously fixed to the dollar, suddenly became “floating” currencies as well. (Note: It did not take long for this new system of floating currencies with floating exchange rates to attract manipulation by speculators and hedge funds. Currency speculation is, and remains, a threat to floating currencies. Proponents of a single global currency use the current manipulation of currency speculators to promote their agenda.)

In this new era of floating currencies, the U.S. Federal Reserve, America’s central bank, had finally freed itself from the constraint of a gold standard. Now, the U.S. dollar could be printed at will — without the fear of not having enough gold reserves to back up new currency production. And while this new-found monetary freedom would alleviate pressure on America’s gold reserves, there were other concerns.

One major concern that Washington had was regarding the potential shift in global demand for the U.S. dollar. With the dollar no longer convertible into gold, would demand for the dollar by foreign nations remain the same, or would it fall?

The second concern had to do with America’s extravagant spending habits. Under the international gold standard of Bretton Woods, foreign nations gladly held U.S. debt securities, as they were denominated in gold-backed U.S. dollars. Would foreign nations still be eager to hold America’s debts despite the fact that these debts were denominated in a fiat debt-based currency that was backed by nothing?

How you can profit from the petrodollar collapse

Download entire 50 pages PDF article series, and also get Exclusive deals, early access to new product releases, cutting-edge trend research, and our weekly podcast

Ready to Read Part Two?

In part two of this four-part series, you will get an in-depth look at the solution that President Nixon and his Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, developed to prevent a continual decrease in global dollar demand. The ingenuity of this plan is breathtaking in scope. It is known as the Petrodollar system. Once you understand this “dollars for oil” arrangement, I believe that it will provide you with a more accurate understanding of what motivates America’s foreign policy.